Pinay scientist devotes life to discovering cancer cure from depths of sea

MANILA—At 64 years old, Dr. Gisela Concepcion is just a year shy of retiring from university work, and perhaps several years away from finding a cure for cancer or another disease.

|

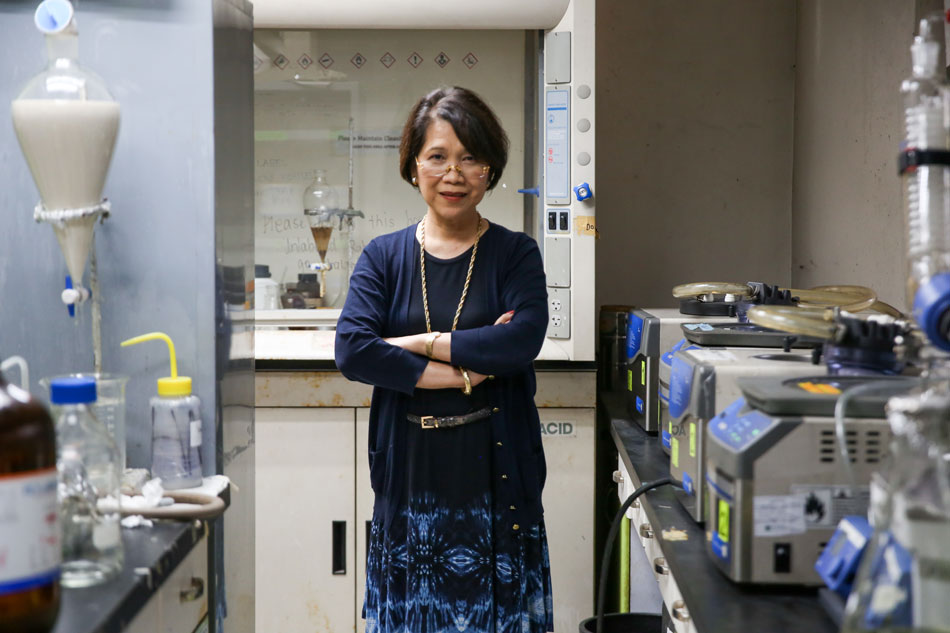

| Dr. Gisela Concepcion at her laboratory inside University of the Philippines' Marine Science Institute. Jon Cellona, ABS-CBN News |

At her lab at University of the Philippines’ Marine Science Institute, we watch her quiz her research assistants on their latest work.

A Ph.D. student from abroad shows off small vials of colored liquid, solvents extracted from various sea creatures, while one graduate student unwraps a white elongated shell of a giant shipworm (tamilok) from layers of bubble wrap. He points us to a large jar filled with a dark yellow chemical and cut up parts of the shipworm discovered a couple of years in Mindanao.

Concepcion walks from room to room, pointing out interesting equipment or specimen. At one point I ask about a caricature of a bespectacled professor drawn on a glass window. “Maybe that’s me,” she chuckles.

Her research assistants are obviously at ease with her, eager to please the former UP vice president for academic affairs.

Falling in love with chemistry

Because her mother died while she was just 7 years old, Concepcion credits her father for motivating her and her 5 siblings when it came to their studies.

Her father predicted that she would become a pharmacist or someone who made health products. It wasn’t surprising since she came from a family of doctors.

But in high school, she was more interested in mathematics. Her love for science only started when she was introduced to chemistry by a teacher who saw her talent.

Her father predicted that she would become a pharmacist or someone who made health products. It wasn’t surprising since she came from a family of doctors.

But in high school, she was more interested in mathematics. Her love for science only started when she was introduced to chemistry by a teacher who saw her talent.

“I felt that chemistry would explain the diversity of materials and substances in the natural world in a way that Physics would not,” she says. “I really liked to understand it (the natural world) in terms of molecules.”

After she graduated as valedictorian, she got into the scholarship program of the National Science and Development Board (NSDB), now the Department of Science and Technology.

Because it was a government scholarship, she enrolled at University of the Philippines as a chemistry student.

Introspection

“I didn’t really have friends in UP. I was alone most of the time. I spent a lot of time in the library then I was just focused on my courses,” says Concepcion, who described herself as being the “nervous type.”

“I guess because my mother died I couldn’t understand why I lost my mother so my tendency as a person is to be pensive, to be introspective. That grew in UP.”

It was during this time that she met renowned English professor Concepcion Dadufalza, who taught her “philosophy and introspection.”

“I learned how to think about the bigger picture by reading all kinds of articles, novels, poems,” Concepcion says.

She immersed herself not only in chemistry but also books and ideas.

Looking away, she says, “I guess I was an insecure person at that time.” She pauses, laughs nervously then adds, “I won’t say that that was the happiest time in my life. I would say that now is better than before.”

That day, Concepcion did not look insecure at all.

In the past decade, she has served as UP vice president for academic affairs and has become a staunch member of the Philippine-American Academy of Science & Engineering.

All these because of her decision to stay at UP and to eventually pursue marine science.

Juggling career, family

But before that, Concepcion faced challenges as she juggled both her career and her family life.

She was in the middle of her Masters in Biochemistry when she married her husband. She finished her master’s degree before she had her fourth child.

In the middle of growing a family, teaching at UP and pursuing graduate studies, Concepcion started working on marine sponge research with the prodding of her mentor, Dr. Lourdes Cruz, another female scientist who is prominent in her field.

Concepcion started reaching out to scientists in the United States and collaborated with marine experts there.

“There was one time I went there with my four kids,” she says. “I was doing that through my wedded and family life. I had to continue my career, which was a challenge for women.”

During this time, she was already pursuing a Ph.D. in Chemistry.

“When I defended my dissertation, I was pregnant with my fifth child,” she says.

Concepcion says her extended family helped her a lot, as in the case of other Filipino families.

“The women here (in the institute) are not just single women. There are also women who are wives and mothers,” she says. This is why she is very patient with other people — knowing that mothers like her struggle more just to finish their graduate studies.

Searching for a cure

Now at UP Diliman’s Marine Science Institute with Cruz, she pursued the relatively new but promising field of marine chemistry.

For her dissertation, she presented “8 new compounds from marine sponge that had anti-cancer activity.”

“The field of marine natural products at that time was maybe 10 to 15 years old,” she says. “It was so promising. Why? Many of the drugs for cancer come from bacteria, fungi and plants. Historically these organisms from land are already studied.”

On the other hand, marine organisms, especially those from the Philippines, have not been thoroughly studied yet.

“Today, that early research has found applications in very serious diseases, in cancer,” Concepcion says.

At one point, Concepcion headed the Philippine PharmaSeas Drug Discovery Program. The financial grant allowed them to further their studies and tap the country’s marine biodiversity as competitive advantage. PharmaSeas produced several scientific publications and promising leads for anti-pain and anti-cancer agents.

However, she explains that the process is both tedious and long.

Collecting specimen is just as challenging as they need to go on dives or have professional divers help them. They also have to get permission from the government and the local communities before taking sponges and other organisms from the sea.

Saltwater then has to be removed from the specimen before it undergoes a liquid solvent extraction process. “You could gradually extract different kinds of compounds from those liquid solvents,” Concepcion says.

The compounds then have to be purified and checked for their chemical structure.

“If they look novel then you pursue the research and then hope that it will show anti-cancer activity,” she says.

For the testing phase, the cancer cell lines are treated with the compounds and later the compounds are injected into mice. She said globally it takes at least 15 years for a bioactive natural compound to become medicine.

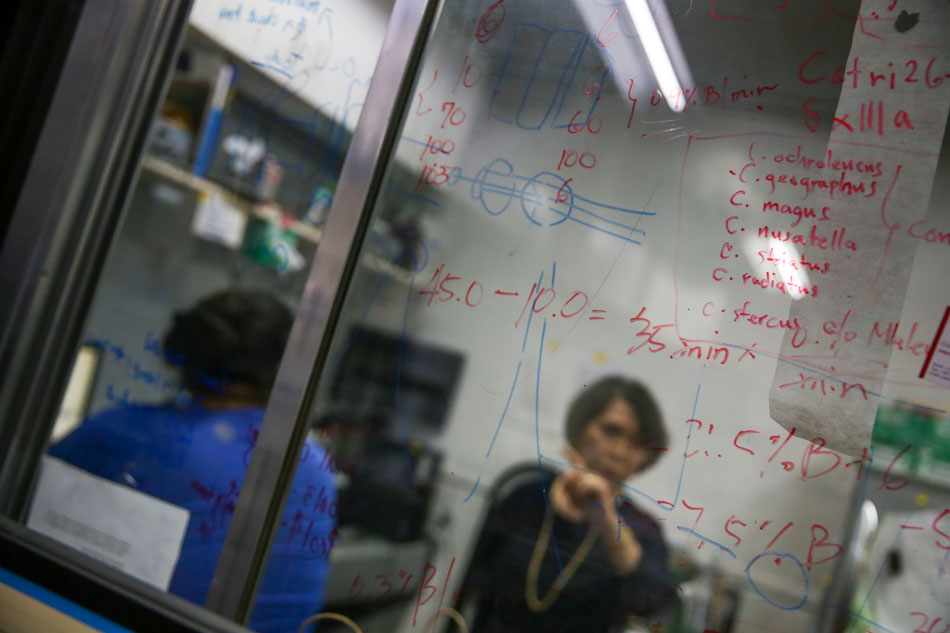

After the sit-down interview, Concepcion brings us downstairs to the laboratory. She allows us to peek into a room that holds their cancer cell lines and marine samples. In another room partitioned by a glass door filled with scribbles of formulas and notes, they show us frog eggs that have been injected DNA encoding neuronal receptors. And next door to that are rooms that smell like the sea filled with tanks that house snails and frogs.

It is incredible to think that the next new medicine for cancer might come from one of these labs.

“To this day, cancer is considered the curse. It’s almost like a death sentence. If you are not able to arrest it in Stage 1 or Stage 2, what is the chance it will not recur?” Concepcion says.

This is why she continues to work hard on her research. Right now, she says, her most important research includes the ongoing testing or renieramycin M from a species of marine sponge. She says it is possible to develop it into an anti-cancer drug, especially since when combined with the existing doxorubicin drug it becomes “very potent.” Currently undergoing animal testing, it also has a pending patent application.

Science advocacy

Concepcion, who will retire soon, says she does not have any plans of extending her full-time work at UP since she wants to give way to younger scientists.

“The new generation they are better-trained than me,” she says, adding that she already has successors in place.

Instead, she will focus on moving forward with her existing research so they can proceed with the animal testing. She says she just wants to protect her intellectual property.

But on top of that, she will continue her advocacy work. Besides maintaining a column for a newspaper, the award-winning scientist has been active in campaigning with the Philippine-American Academy of Science and Engineering (PAASE). Their early work resulted in the allocation of government money for the National Science Complex located in UP.

“(Science) is really the driver of socioeconomic progress. Our only challenge is this: That kind of science and technology-driven economic development must be inclusive,” she says. “It must be first geared towards poverty reduction, hunger reduction and food and nutrition for our youth.”

Concepcion says that besides teaching a class at the UP Open University, she plans to give talks at schools to encourage young Filipinos to pursue science.

“We want to get more Filipinos to understand the process of invention and innovation and to go on the path of discovery,” she says.

Before our interview winds down, an excited Concepcion starts talking about her new research focus — shipworms — worm-looking marine organisms that are related to clams. She has already started looking at how shipworms break down energy from wood.

“My research is not just about drugs. It’s about the marine ecosystem. And these are the possible applications – for biowaste, for recycling,” she says.

Soon she starts talking faster, fired up as she recalls how they found the giant shipworm that was in their lab.

“Parang sewage lake (sya natagpuan). Hydrogen sulfide and meron doon. Walang oxygen. Anong ibig sabihin? Yung bacteria nun nag-evolve,” Concepcion says, explaining that the bacteria in the shipworm probably oxidizes the hydrogen sulfide to get energy. “Anong application nya? Sewage treatment and decontamination.”

(It was found in something like a sewage lake, which was filled with hydrogen sulfide. There’s no oxygen. What does that mean? The bacteria evolved. What is the application for that? Sewage treatment and decontamination.)

And she plans to do all these after her retirement. At 64-year-old, Concepcion continues to find new avenues for research in the Philippines.

For one of UP’s top cited scientists, retirement seems to just be another opportunity to pursue science, as well as advocacy.

No comments:

Post a Comment